Below is the Non-technical Executive Summary of the Penpol Report (survey and research project on the 'The Field') which offers a good introduction to both the Report and Penpol Site.

The CD is no longer available. If you are interested in the Report please email us at [email protected]

The Executive Summary was written by Dr Carol Wellwood, Project Manager of the Survey and Research Project, and Author of the Report.

Non-Technical Executive Summary

Background

Intended as an educational and demonstration site, the Field experiment was begun by Ken and Addy Fern in 1989 on an extremely windy, erosion-prone hillside at Penpol in Cornwall. In the first years, a native woodland Area was planted across the northern, higher half of the Field, and windbreaks of fast-growing trees were established across the southern lower half, rapidly creating a series of sheltered Areas where the Fern’s system of vegan–organic, radically minimal–input, perennial horticulture was implemented in an assemblage of diverse and meticulously thought through planting designs. Initially a communal project, internal dissent on how the land was to be shared has limited participation in the work needed to maintain and develop the designs; currently, Addy Fern manages most of the site with help from a few participants and volunteers.

Aims and methods of the survey

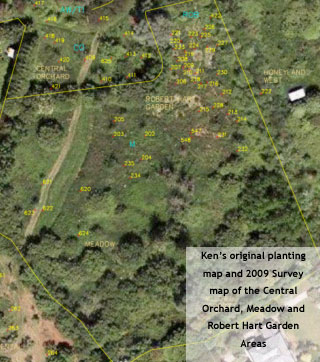

This survey aimed to measure the success of the experiment primarily by assessing the health, development and productivity of the plants and designed ecosystems. Information on the health, history and yields of the noteworthy trees, shrubs and other plants growing in the Field, was mainly provided by Addy, assisted by Ken’s original planting maps, recorded and entered into a spreadsheet, now Appendix 1 of the report. Accurate maps were created with a unique number for each of these plants marked on them.

The Field is divided into Areas naturally defined by the main windbreak hedges, and further divided into compartments where the Areas are themselves divided by hedges.

The survey also aimed to assess the condition of the native woodland, including any potential harvests from it, and to provide a measure of the ecological health of the Field by surveys of the bird and insect life there, as these depend on the condition of the plant life. Interviews with current and previous participants in the Field experiment provided more general information.

Results

The soils of the Penpol Area are slightly acidic, well-drained and moderately fertile, with natural erosion from the top downslope, exacerbated by continued ploughing and modern agricultural practices used on the land prior to the Field experiment. The soil was neutral when the experiment began, indicating it had been limed shortly before.

The windbreaks and hedges have provided the most noticeable improvement to the site, moderating the extremely windy conditions there, creating peaceful, sheltered environments, improving and protecting the soil from further erosion, providing harvests, habitats for wildlife, and, in many instances, soil nitrogen for other plants. Lack of maintenance has, however, caused problems with spreading and overmuch shading over the years.

The division of the site into Areas and compartments by these hedges allows very different planting systems to develop within the Field, although it can increase the maintenance required. It also allows the health of similar plants in different systems to be compared.

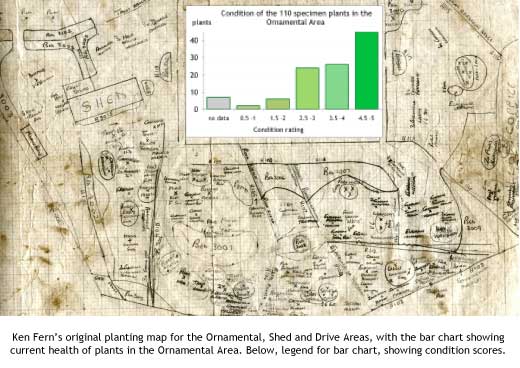

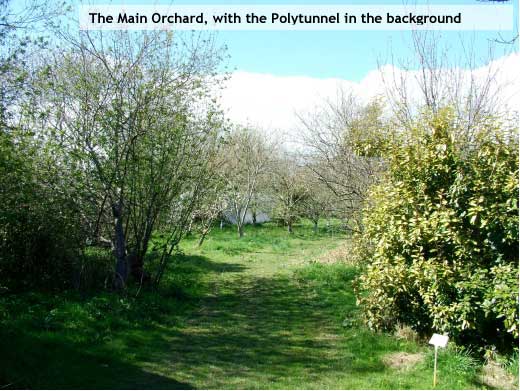

Bar charts are used to show the numbers of healthy and unhealthy plants in each of the Areas and compartments, and in the various kinds of plants at Penpol.

The Areas

The Shed and Drive Area is a narrow strip from the main gate to the Shed, with a mix of fruiting shrubs, trees and vines, yielding fruit, nuts and edible leaves.

The Ornamental Area, south and east of the Shed, is divided into many compartments by hedges that create shelter and suntraps, and was designed to resemble a series of small gardens and inspire visitors to copy some of the planting patterns in their own gardens. It contains a pond, a Winter Salad Bed, and many unusual and exotic plants, some thriving, some struggling. The mixed plantings there yield fruit, edible leaves and flowers, and canes.

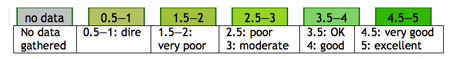

The Main Orchard and Addy’s Orchard, and the smaller Central Orchard were created for the 100 or so apple cultivars that Addy Fern brought to the Field. Although the original design plan was to distribute the successful apple trees in mixed woodland gardens around the Field, Addy has kept them as orchards to minimise maintenance requirements. The apples they provide are the Field’s main crop, which Addy gathers and stores for eating in winter and early spring. The great majority of the Apple trees are on slightly dwarfing rootstock, although some in Addy’s orchard are on a more vigorous rootstock; 21 trees have been grafted with budwood collected from prolific local Apple trees.

The two larger orchards are sheltered by windbreaks running roughly north–south, and divided into compartments by smaller hedges, many of which were originally edged with beds for smaller plants. ‘The Ribery’, planted with various currant bushes, is one of the few beds still extant, and Addy has fenced two small areas of mixed plantings to protect them from deer and rabbits. There is a Polytunnel and a shade/net tunnel in the Main Orchard. Other fruit trees and bushes in these two orchards include Raspberries, various Plum, Cherry and Pear, along with a few more unusual fruit trees.

Grasses predominate in the ground layer of most of the Orchards, although Dwarf Elder has invaded much of one compartment in the Main Orchard. Mowing to control grass and weeds can be infrequent but Addy’s and the Main orchards are kept fairly clear. The Central Orchard, possibly because it is further from the shed, is more shaded and overgrown.

All the Apple trees in the orchards are infected with canker to some degree, and, although most continue to bear quite well, Addy has observed a general deterioration in fruit quality over time, which she suspects is because of low levels of calcium in the soil. Harvested apples remove calcium and other minerals from the land and, as tests indicated the soil in the orchards had become more acid, rainfall may also be leaching calcium and other minerals from the topsoil. Other causative factors may have included shading from the over-tall windbreaks, which have now been pollarded.

All the Apple trees in the orchards are infected with canker to some degree, and, although most continue to bear quite well, Addy has observed a general deterioration in fruit quality over time, which she suspects is because of low levels of calcium in the soil. Harvested apples remove calcium and other minerals from the land and, as tests indicated the soil in the orchards had become more acid, rainfall may also be leaching calcium and other minerals from the topsoil. Other causative factors may have included shading from the over-tall windbreaks, which have now been pollarded.

The Meadow is a fairly open area south of the Central Orchard, mainly long rough grass around Seabuckthorns and young self–sown native trees. Initially, only the Poplars and Willows of the coppice that extends over its southern part, were planted there. A number of the poplars are moribund but others are thriving.

The Robert Hart Garden was begun in 1999 in memory of Robert Hart, who initiated Forest Gardening in the UK, and from whose garden some of the plants came; it is tended by Phil James. A Forest Garden is planted to mimic a young forest or forest edge, with trees, shrubs and herbaceous plans chosen to occupy up to seven layers of vegetation, ranging from large canopy trees, to groundcover, roots and climbers.

The Robert Hart Garden was begun in 1999 in memory of Robert Hart, who initiated Forest Gardening in the UK, and from whose garden some of the plants came; it is tended by Phil James. A Forest Garden is planted to mimic a young forest or forest edge, with trees, shrubs and herbaceous plans chosen to occupy up to seven layers of vegetation, ranging from large canopy trees, to groundcover, roots and climbers.

The widely spaced canopy trees include Apple, Monkey puzzle, Whitebeam and Plum trees, with a bush layer consisting mostly of fruit bushes, such as Red and Blackcurrants, and Mint, Fennel and other herbs in the ground layer.

The Old Veg and Nursery area is roughly square, and was originally planted in well-defined vegetable, soft fruit and nursery beds. Many of the Currant and Gooseberry bushes survive and provide fruit for birds but the Raspberries have not fared well there. It has become very overgrown, and much of it is shaded by tall trees, even some of the smaller, fruiting Thorn trees planted amongst the soft fruit to create a woodland garden. In sunny patches, a Grape vine and various Kiwis ramble and climb through the trees.

Directly north is the New Veg and Nursery Area, larger and less overgrown, with various fruiting trees, including Seabuckthorn that bear prolifically from August, and four young, healthy Apple trees, on vigorous rootstock.

Directly north is the New Veg and Nursery Area, larger and less overgrown, with various fruiting trees, including Seabuckthorn that bear prolifically from August, and four young, healthy Apple trees, on vigorous rootstock.

The easternmost areas, Honeylands and Eastern Rabbit, were not surveyed; they are very overgrown and no longer contain any significant plants.

The three Arboretum areas, north of the east-west central Track, are under the stewardship of people other than the Ferns.

Arboretum East is open-canopied at its southern end, where a group of Apple trees, some on vigorous rootstock, have been well-mulched and kept clear, although some are shaded by windbreaks. To their north is a belt of Hazel and Cob nut trees, and beyond them various Walnut and Oak trees creating a relatively uncrowded canopy, with patches of Bamboo and Raspberries, self-sown Willow and Elder trees growing under. A Grapevine climbing through and along the boundary hedge is in excellent health but its fruit is unlikely to ripen in the shady conditions.

Arboretum East is open-canopied at its southern end, where a group of Apple trees, some on vigorous rootstock, have been well-mulched and kept clear, although some are shaded by windbreaks. To their north is a belt of Hazel and Cob nut trees, and beyond them various Walnut and Oak trees creating a relatively uncrowded canopy, with patches of Bamboo and Raspberries, self-sown Willow and Elder trees growing under. A Grapevine climbing through and along the boundary hedge is in excellent health but its fruit is unlikely to ripen in the shady conditions.

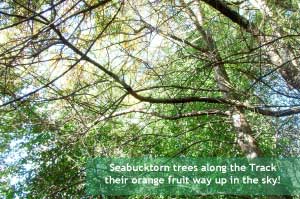

Parts of Arboretum Central, especially in the middle of the area, are so overgrown as to be impassable.  The taller trees, including quite a few Pines, create a fairly dense canopy in places, and although patches of Dogwoods are spreading and fruiting there, nearby Brambles have been shaded out. In the more open southwest part, tall Willows cast deleterious shade on some of the smaller trees, including Hawthorns, Whitebeams, Rowans and Pears, and the group of young Monkey puzzle trees to their north. Some of the Chestnut trees in the northern part are bearing nuts. Further east along the Track, the Field’s original Seabuckthorn plantings have now grown very tall and their fruit is far too high up to harvest.

The taller trees, including quite a few Pines, create a fairly dense canopy in places, and although patches of Dogwoods are spreading and fruiting there, nearby Brambles have been shaded out. In the more open southwest part, tall Willows cast deleterious shade on some of the smaller trees, including Hawthorns, Whitebeams, Rowans and Pears, and the group of young Monkey puzzle trees to their north. Some of the Chestnut trees in the northern part are bearing nuts. Further east along the Track, the Field’s original Seabuckthorn plantings have now grown very tall and their fruit is far too high up to harvest.

Frank Schuurmans manages the Arboretum West area quite intensely, creating alternating clear and shaded areas around trees planted in groups of three to six specimens. Near to the Track are Dawn redwoods, various Eucalyptus trees and a hedge of Cherry plums. Further in, nut and fruit trees grow around and below taller canopy trees and self-sown Willows. These include Sweet chestnuts, Birch trees, Poplars, various successfully-grafted Thorns, and several Pear trees, planted as experiments, that produce blossom but no useful fruit. In the more open areas, ground layer plants grow vigorously, indicating how fertile the soil has become. Many of the pines and firs in the northeast of the area have not survived encroaching brambles.

The Native Woodland and Coppice Areas occupy the northern half of the Field, and were planted in the first years of the project, predominantly with native trees, to create woodland habitat for a nature reserve. The Coppice was intended to provide woodland harvests. The westernmost part of this wooded area now belongs to friends of the Ferns’. The main tree species there now are Oak, Sycamore, Ash, Goat willow, Beech and some Hawthorn, with significant natural regeneration, including Gorse, Ash and Elder. Many Willow trees and Brambles have been outgrown by larger trees and are dying off, as part of the process of natural succession. The many trees planted have created an overall effect of young woodland beginning to establish, despite damage by deer, rabbits, squirrels and other wildlife. Some very close grown areas would benefit from thinning, especially to save interesting specimens and encourage trees to fruit.

The New Nursery Area (‘Rebel Land’) was completely impenetrable in summer 2009, although Phil James has recently made some paths through the brambles, which he likes to leave untouched until access is needed, as it protects the trees growing there from deer damage.

In 1997, he walked from St Kevern, Cornwall to London, to commemorate the Cornish Rebellion. He bought the trees for this area with the money he raised on the walk.

The Plants

One aim of Ken Fern’s designs was to place plants in environments naturally suited to them, where they would thrive and produce crops with minimal care and effort. The majority of the plants recorded in the survey are healthy; many of those thriving at Penpol are particularly suited to areas with a temperate maritime climate and shadier environments, such as a Forest Garden. Many are succeeding in difficult environments, where there is a lot of competition for water, light and nutrients.

Where there are more than ten recorded specimens of a plant family, bar charts are used in the report to illustrate their overall health. Those that have flourished most include the Seabuckthorns, which provide a harvest yearly, the Elaeagnus, some of which fruit quite well, the Amelanchiers, whose fruit is nearly all taken by birds, and the Walnuts which grow mainly in the Arboreta, and whose fruit is not gathered.

Where there are more than ten recorded specimens of a plant family, bar charts are used in the report to illustrate their overall health. Those that have flourished most include the Seabuckthorns, which provide a harvest yearly, the Elaeagnus, some of which fruit quite well, the Amelanchiers, whose fruit is nearly all taken by birds, and the Walnuts which grow mainly in the Arboreta, and whose fruit is not gathered.

Most of the Plums, Monkey puzzle trees, Thorns and Barberries are healthy; the Apples, Cherries, Whitebeams and Rowans are doing reasonably well, slightly better than the Dogwoods, Pears, Hazels and Currants.

The 162 Apple trees recorded at Penpol include more than 70 identified cultivars; numerous Apples were grafted by the Ferns with budwood from promising trees, many local, with some good results. The fruit from some Apple trees did not ripen or keep as well as previously, or as those from the budwood source tree, or had become biennial rather than annual fruiters over time.

The 162 Apple trees recorded at Penpol include more than 70 identified cultivars; numerous Apples were grafted by the Ferns with budwood from promising trees, many local, with some good results. The fruit from some Apple trees did not ripen or keep as well as previously, or as those from the budwood source tree, or had become biennial rather than annual fruiters over time.

There are several large-fruited Thorn trees in the Ornamental Area and Addy’s Orchard, and numerous wild Hawthorns elsewhere, including in the Native Woodland and Arboretum Areas.

Ken considers Elaeagnus family of shrubs really important for the Field. They fix nitrogen in the soil, make “an amazing hedge”, and produce fruit that all children like, especially the deciduous species. There are good or prolific fruiters in the Ornamental Area, the Main Orchard, Addy’s Orchard and the Robert Hart Garden.

The Seabuckthorns have been consistently prolific fruiters at the Field whilst, as nitrogen fixers, they add to the fertility of the soil around them. Trees in the New Veg and Nursery Area, Meadow, Main Orchard and Robert Hart Garden provide harvests from August until mid February, depending on bird predation.

Ken Fern states that the various shrubs of the Juneberry (Amelanchier) family succeeded “reasonably well” in the early years of the Field but, as the tree cover increased, no longer fruit very well. They will tolerate partial shade but fruit best in full sun and are subject to relentless bird predation. Two specimens, growing in the Ornamental Area and Addy’s Orchard, yield well.

Ken Fern states that the various shrubs of the Juneberry (Amelanchier) family succeeded “reasonably well” in the early years of the Field but, as the tree cover increased, no longer fruit very well. They will tolerate partial shade but fruit best in full sun and are subject to relentless bird predation. Two specimens, growing in the Ornamental Area and Addy’s Orchard, yield well.

Many of the Barberry shrubs at Penpol form part of hedges; there are fruiting bushes in the Main Orchard, near the Shed, in the Ornamental Area and Arboretum East.

There are at least eight kinds of Plum growing at the Field, including Plum, Cherry and Cherry plum trees. Plums grafted with budwood from two local trees, apparently of the same variety, are occasionally prolific and have a long harvest of very nice, yellow, damson-sized plums from August. There are trees of this cultivar in Addy’s Orchard, the Ornamental Area and the Central Orchard. A young Morello Cherry tree in Addy’s Orchard bore its first four cherries in 2009; other Cherry trees recorded at Penpol either bear disappointingly bitter fruit or have not been observed to fruit. None of the Cherry plums are prolific, although a Damson in the Robert Hart Garden fruits well sporadically.

There are at least five kinds of trees of the Rowan family growing at Penpol but only the two Whitebeam trees in the Robert Hart Garden fruit well, with pleasant fruit. Rowan trees have been planted throughout, including in the Main and Addy’s Orchard but the fruit they bear is neither good nor abundant.

There are three or four kinds of Pear at Penpol, including several unidentified seedlings. Only one, in the Main Orchard, yields well, although the fruit does not taste particularly good.

The Dogwood family has several species with edible fruit, at least five of which are growing at the Field; the only ones producing pleasant-tasting fruit are the Japanese dogwoods in the Ornamental Area.

The Dogwood family has several species with edible fruit, at least five of which are growing at the Field; the only ones producing pleasant-tasting fruit are the Japanese dogwoods in the Ornamental Area.

There are both wild and cultivated Hazel and Filbert trees, with six named cultivars in Arboretum East; only two are cropping, a ‘Kentish Cob’ in Arboretum East and an unidentified cultivar in the Robert Hart Garden.

None of the Plum yew shrubs on the Field were identified, and so far, none have borne fruit; all the bushes mature enough to do so are apparently male.

Monkey puzzle trees are an investment in the future; none of those growing at Penpol appear ready to fruit, although some are approaching 20 years of age.

There are at least ten kinds of Currants still growing at the Field, with eight of the sixteen different species planted in the Ribery surviving. Only the Blackcurrants in the Robert Hart Garden and the Redcurrant in the Ribery are fruiting reasonably well.

There are three kinds of Walnut at the Field, English, Japanese and Heartseed walnut, growing in the Arboretum Areas, the Robert Hart Garden, the Main Orchard, and one in the Ornamental Area. One Japanese walnut has been fruiting for some years but the nuts are small and it is hard to extract much meat from the shell; an English walnut in Arboretum West flowered for the first time in 2009

There are two kinds of Chestnut tree at the Field, Chestnuts, including two ‘Marron de Lyon’ cultivars, in Arboretum Central and Addy’s Orchard, and Chinquapin, growing in a group in the Ornamental Area. None are harvested.

There are two kinds of Chestnut tree at the Field, Chestnuts, including two ‘Marron de Lyon’ cultivars, in Arboretum Central and Addy’s Orchard, and Chinquapin, growing in a group in the Ornamental Area. None are harvested.

The report makes brief comments on other plants of interest at Penpol, including Crab apples, Holm oaks, Kiwi and Grape vines, various Raspberries, ‘Blue sausage fruit’ shrubs, various Bamboos and edible ground layer plants, such as Bellflowers, Day lilies, Babbington’s leeks, a Yacon growing in the polytunnel, and three kinds of trees not planted as specimens, namely Wych elms, Willows and the extremely successful windbreak Alders.

Companion planting

Ken Fern designed many areas with individual plants dispersed and interplanted, sometimes with ‘sacrificial’ ones, to protect yields from predation but, in Addy’s experience, dispersed plants do not keep their fruit much longer. She has done her own interplanting experiments, creating two mixed beds, which she has found interesting to watch as plant relationships change over time. She has found that the main problem with mixed plantings has been that the more vigorous plants expand and suppress the less vigorous ones, unless cut back.

The Breeding bird and Invertebrate surveys

The wildlife surveys have found the Field far more wildlife friendly than the “species poor” agricultural countryside surrounding it, and commented on the thoughtful design and structural diversity there.

The ornithologist Peter Kent remarked that it made “a valuable contribution to supporting bird communities”, and entomologist Patrick Saunders described it as “a site of conservation interest”. Both said they really liked the place and were impressed with its transformation.

Discussion and comments on results

A major aim of the survey was to identify and record as much information as possible about significant plants at Penpol; the plants were chosen for how well they had fared in the low–input, minimal–management regime there, although not all were currently productive. The main limitation was that only those plants that Addy Fern, Phil James or Frank Schuurmans were familiar with could be included. The evaluation of yields and plant health was of necessity qualitative. In most permaculture gardens, harvests are gathered over time, rather than in one instalment, which makes qualitative assessment of yield by those harvesting seem the only practical method, although the basis for what is essentially a comparative measure must be carefully and clearly explained.

Repeated surveying of significant plants during flowering, fruiting and dormant seasons would yield more detailed information but was not possible, partly because of unusually poor and wet weather, and the limited availability of Addy, Phil and Frank.

Liz Turner’s Scoping Study (Appendix 2a) set out the initial ground rules for the survey, and proved remarkably accurate on the time required for each area. Surveys of other sites, especially if large, would benefit from a similar study.

Record keeping is important for all Permaculture projects, and those of Ken Fern’s maps and notes that were available, proved useful. They recorded the original designs and planting schemes, allowing changes, whether by default or design, to be followed. However, because the survey’s identifying codes for specimens on the Field cannot easily be correlated with those Ken Fern used, much information has effectively been lost.

The continued keeping of a journal, diary, or monthly notes on specimens in the Field would have increased the detail and usefulness of available information, although consistent, easily understood and updated records are preferable. The best format for keeping updates is a personal choice, with many possible approaches. Clearly labelled, dated photographs, initial and recurrent soil tests, and good maps that ensure plants are easy to locate, are all recommended.

Clive Williams’ excellent maps are an investment in the future of the Field, making it easy to find specimens and update the research information. However they were costly to produce and may not be appropriate for other sites.

Liz Turner’s survey of the Native Woodland and Coppice areas found significant natural regeneration of native species, and the process of natural succession commencing. Her management recommendations would ensure the survival of interesting specimens and increase the productivity of the areas without compromising their wildlife value.

Building up Soil fertility in the Native woodland Area:

natural leaf mulch (above) and undergrowth (below)

The health of an ecosystem on any site is reflected in the number and variety of species of animals inhabiting and using it. The limited Breeding bird and Invertebrate surveys proved an inexpensive way of assessing the ecological health of the Field and comparing it to the agricultural land surrounding and preceding it.

The interview questionnaire (Appendix 9) proved a useful framework for the interviews, eliciting quite detailed information on the aims and progress of the designs, and changes in the management of various areas over the years.

The Field experiment has shown that some plant families grow and fruit well in the Southwest’s maritime climate; others will grow and thrive but sometimes do not fruit well. In some, only certain named varieties yield worthwhile fruit.

There is great potential for propagation from plants growing at Penpol, for use on the Field or export from there; suitable plants are listed in the report section titled “The plants”, although identifying which plants are in demand would need some market research. Allowing the pre-ordering of plants, especially online, could be profitable.

Some trees in the Native woodland are producing viable seed but seedlings can vary immensely, especially in yield; runners, cuttings and budwood for grafts, effectively clones, are certain to be identical to source plants. Where seedlings are of fruiting age, as in some of the hedges, the best specimens can be selected for taste and yield and propagated. Rootstocks suitable for grafting onto can be found in planted seedlings and natural regeneration in the Arboretum areas and Native woodland.

The possible causes of the progressive deterioration in quality of some apples include shading from the windbreaks and hedges in the Orchards, most of which have now been pollarded, and the acidity found by soil tests there. Various factors could be contributing to this acidity, including the high rainfall in the region, increased organic matter in the soil, the removal of alkaline elements in the fruit crops and any quantities of windfall apples left to lie and decay under the trees. This acidity undoubtedly affects the health of the trees and the quality of their fruit, and should be investigated, especially since it might be happening elsewhere on the Field. The orchards need more inputs to stay healthy, even if the grass was mown more often; planting many deep-rooted perennials that accumulate minerals could help.

Overview and conclusions

The Field was originally intended as an experimental, educational and demonstration site for sustainable, minimal-input, vegan–organic, wildlife–friendly permaculture. It is unique in terms of size and longevity, and has proven that this radical regime can transform a windblown, eroded agricultural ‘desert’ into a verdant, fertile, sheltered landscape, producing food, providing wildlife habitats, and increasing soil organic matter, without inputs of synthetic or animal manures. It also has probably the lowest carbon footprint of any food producing system. However, as the current management problems demonstrate, it has not proven that this improvement is sustainable, nor that harvests of any significant scale are obtainable over the long term. There are two main reasons for these unresolved issues, the lack of planning permission, which prevents anyone living on the site, and the lack of proactive management, arising from conflicts over the rights and responsibilities of the people involved. For Ken, the Field was an experiment intended to evolve and change over time, allowing the site to continue developing, but the changes have often not been implemented, to the detriment of plants, productivity and design sustainability. Forest gardens need their canopies kept fairly open to remain productive. For Ken, the balance of emphasis has shifted from food production function to wildlife sanctuary, and, although he would like to see the Field restored as an educational and demonstration area, he is “really, really pleased with what has happened there”, as the health of the land has been restored.

Addy Fern continues to work hard to achieve year–round edible harvests from the Field, and prevent its degeneration into impassable scrub and woodland overrun with Brambles, whilst respecting both the original design plans and the incoming wildlife. She manages the Orchards, and some others areas without significant help. She has created some mixed woodland garden beds that are working well, but has not developed or altered Ken’s designs. She keeps her Apple trees and other fruiting plants grouped in the Orchards and elsewhere, in order to give them the focused attention she believes they need to provide reasonable harvests, but does little to protect fruiting trees from birds. She believes a large and potentially expensive fruit cage is needed to obtain good harvests.

For Addy, the Field is predominantly a source of fresh, vitally healthy food, produced according to vegan organic ethics, “without poisoning the environment, killing or causing to kill”. However, simple conservation of the Field as it stands, is not possible, because the plantings will, and always were intended to change as the systems matured. If the Field is not managed, it will not only lose its value as a vegan–organic experimental site but will also deteriorate as a wildlife habitat.

For Penpol to become more than a memorial garden to a good idea, which effected enormous change on the landscape, its natural fertility and productivity, but was ultimately unsustainable, it needs rejuvenation and some aggressively proactive management. The experimental and educational facets of the site need to be developed, because the Field’s relevance will increase as demand for resources outstrips limited supply and generates constraints on agricultural inputs. It is currently impossible to manage it effectively without contravening the low input ethic, part of which is the avoidance of car usage.

The Field offers many opportunities for research into sustainable, low–input food production but no controlled experimental plantings have so far taken place and identical plants in different areas are of different ages or varieties, and difficult to compare. There are, however, notable differences in the overall health of the plants in different areas, with the Ornamental Area, the Meadow, Robert Hart Garden and part of Arboretum West having greater percentages of healthy plants. This may be a result of similarities of design, planting or density in these areas, which are nearly all open-canopied with mixed plantings. Because of its size, diversity and maturity, the Field is an ideal place for studies on the co–existence of food producing ecosystems and wildlife, and on building up soil fertility without using fertilisers. It also offers sufficiently diverse environments in which methods for identifying the best plants to grow in any given climate and situation can be developed.

The Field offers many opportunities for research into sustainable, low–input food production but no controlled experimental plantings have so far taken place and identical plants in different areas are of different ages or varieties, and difficult to compare. There are, however, notable differences in the overall health of the plants in different areas, with the Ornamental Area, the Meadow, Robert Hart Garden and part of Arboretum West having greater percentages of healthy plants. This may be a result of similarities of design, planting or density in these areas, which are nearly all open-canopied with mixed plantings. Because of its size, diversity and maturity, the Field is an ideal place for studies on the co–existence of food producing ecosystems and wildlife, and on building up soil fertility without using fertilisers. It also offers sufficiently diverse environments in which methods for identifying the best plants to grow in any given climate and situation can be developed.

With its supply of rootstock sources for unusual fruiting species, Penpol could also become a UK base for importing cuttings from suitable cultivars, and could provide rare and unusual plants for our future.

Recommendations

Research and management

The variety of ecosystems at Penpol offers opportunities to compare plant vigour and yields under different management regimes.

Because the designs for the Field are complex, and the areas involved large, a manager is needed to take responsibility for overseeing any research and study, and would need to live within easy walking distance. The same is true of students whose research or study course requires more than one day at Penpol. An on–site office, where enquiries are dealt with on a daily basis, is also a needed if any liaison with educational or horticultural establishments are to be initiated and maintained. The lack of available local accommodation makes residential planning permission the logical and, environmentally, lowest impact solution.

If Penpol is to function as it was intended, good record keeping is essential. The best format for records will depend on the person responsible but must be easy to update and understand, and linked to the survey maps. The manager/record keeper should develop a clear method of transferring botanical information from the Field to the new PFAF website.

A programme of clearing, thinning and replanting is recommended; indeed, many of the designs for the Field were intended to be fluid and change over time. A far more proactive approach is needed to identify the best species and cultivars.

Balance of food for humans and wildlife

The ethic of sharing the Field and its produce with wildlife is an important part of the design but fruit cages are necessary if humans are to harvest anything more than token amounts from many of the plants. Such cages need not enclose all the trees and bushes of a kind, nor deny ample harvests to the birds. Many tree trunks there are protected from deer and rabbits, without apparently driving them from the land, so the protection of some fruit from birds would not transgress Penpol’s vegan ethics, and is recommended if increased human involvement is to succeed.

Propagation

Along with botanical information, plants are the Field’s greatest and most marketable assets and potential products. Some are quite rare, and all plants propagated from those at the Field would undoubtedly benefit from the added prestige of their origin and the association with the Ferns and Plants for a Future. Some market research into demand will be necessary before beginning any large–scale propagation.

Import and experiment with suitable cultivars

The degree of success in experiments with productive plants could be significantly enhanced if Penpol can import interesting new cultivars of fruiting species, even those that require vegetative propagation, from countries where new selections and breeding of particular plants is taking place. Once trialled, the best cultivars could then be introduced to the rest of the country, or continent.

Teaching

Facilities for educational programmes, especially the ‘teaching by doing’ courses once undertaken at Penpol, are an essential part of communicating the lessons of the Field, and need to be developed so that they are less weather-dependent, and can proceed despite periods of inclement weather characteristic of so many Cornish summers. Ken Fern envisaged a classroom under cover but not closed off from the Field, which would be ideal. An office to ensure consistent communication with students and educational establishments, and storage space for students’ instruments and provisional records are also essential to accommodate any enhancement in teaching.

There is much yet to be learnt from Penpol.